"Red Pill" by Hari Kunzru

A Review

At the start of the novel, the unnamed protagonist

of Hari Kunzru’s Red Pill admits that he is going through a mid-life

crisis. He is a moderately successful academic and writer, who lives in

Brooklyn with his wife Rei, a human rights lawyer, and their three-year-old

girl. Yet he feels unfulfilled and increasingly anxious about the state of the

world. This continuous state of anxiety places

a burden on his marriage and saps his creativity. Then the opportunity arises for him to spend

a few months at the Deuter Centre, situated on the Wannsee in Berlin. This could

be a perfect opportunity for him to reboot. Rei actively encourages him to spend a few

months away from home – provided he comes back ‘whole’.

The Deuter Centre, however, turns out to be quite

different from what he expects. The

Centre is situated close to the villa where, at the “Wannsee Conference” Reinhard

Heydrich outlined his nefarious “final solution

to the Jewish question”. And although

the ideals of the Deuter Centre, founded by an ex-Wehrmacht general, appear to

be in direct opposition to Nazi-Fascist thought, the Centre’s “forced” communal

approach and disturbing surveillance measures are not worlds away from the

strictures of an extremist regime.

The narrator’s sense of oppression grows and

turns into paranoia. Even as he works on a treatise on the “lyric I” in German

Romantic literature, he increasingly questions not only his own self, but also

the very basis of the value we give to human life and human dignity. Things come to a head when the narrator makes

the acquaintance of Anton, a film director who has gained notoriety for a

violent cop series airing on German TV. The narrator is horrified but not too

surprised to discover that Anton is a leading figure of the alt-right. Through him, the narrator discovers a subversive

hostile culture that plans to dominate the world in increasingly unsubtle ways. As the narrator’s sanity unravels, he

believes himself to be in a personal battle with Anton and all he

represents. But is this all just paranoia

or is truth closer to a nightmare than we are ready to admit? There are certainly some autobiographical

touches in the novel which suggest that the narrator’s fears are not that

far-fetched.

On his arrival at Wannsee, the narrator, almost

literally, stumbles upon the grave of Heinrich von Kleist. Kleist, one of the exponents of the German

Romantic movement, was hugely influenced by the philosophy of Immanuel Kant which

he came across in 1801. This shaped Kleist’s

subsequent literary career, but also cast a tragic shadow upon his life. In fact, Kleist interpreted Kant’s view as

implying the impossibility of ever establishing an objective truth. This led him into the dark alleys of an existential

crisis from which he never fully recovered.

He would eventually die by his own hand, in a murder-suicide planned

with Henriette Vogel.

Kleist looms large in the novel and, indeed, the

vicissitudes of his life could be the key to understanding the predicament of

the narrator. Kleist’s unhappiness at

his lot could, at one level, be deemed to be a pathological condition – the narrator

himself, at one stage, floats a theory that Kleist suffered from PTSD. But

there is no denying that Kleist’s crisis was also an existential one, born out

of a legitimate philosophical concern.

The same could be said of the narrator’s crisis

which is not only pathological but also an existential one. More importantly, it is possibly a crisis

which all men of goodwill should be going through at the moment. Faced with inequalities,

injustice, human suffering, the refugee crisis, the trampling of fundamental

freedoms and the resurgence of the far-right, can we really discount the

narrator’s fears as mere paranoia?

|

| The villa where the infamous Wannsee Conference was held |

“Red Pill” invites discussion not just thanks

to its subject matter, but also through its approach. Although, at first glance, the narrative

appears a relatively linear one, the novel becomes exhilaratingly complex

thanks to its riot of cultural references.

It is haunted by the ghosts of German history and 19th century Romanticism, but its web of associations draws into it some other unlikely bedfellows.

Thus “Red Pill” of the title is specifically alluded to only once in the text –

but that is enough to link it to the choice between the “blue pill” of blissful

ignorance and the “red pill” of truth mentioned in the movie “The Matrix”. And besides that, there are more abstruse

references to political philosophy and figures of the Enlightenment and

Counter-Enlightenment. I would be comfortable describing this as a “novel

of ideas”, but it could equally be considered a psychological thriller, an

adventure story, a romance or, even, a dark comedy. And, as a lover of the Gothic, I could not

help also perceiving echoes of the German Romantic sub-genre of the “secret society novel”, variously referred to as the Bundesroman or the Geheimbundroman. This reference is suggested by the narrator’s

increasingly feverish research into the “dark web” and the far-right groups

which haunt it – an aspect of the book which reminded me also of Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s

Pendulum and Numero Zero.

Admittedly, the plethora of "meta-levels" sometimes

make the novel seem unfocussed. In particular, I have in mind the segment of

the book describing the experiences of Monika (the Deuter Centre’s cleaner)

under the GDR. Taken on its own, it makes for a harrowing and moving read. It also fits in well with the narrator’s

concern about the “surveillance regime” adopted at the Centre. In the context of the whole book, however, the

need for it is not too clear. Perhaps

Kunzru’s idea is to show us that danger of extremism is not limited to the

right end of the political spectrum. But then

again, the novel neither invites nor provides clear answers, and is so much the

better for it.

Kindle Edition, 320 pages

Expected publication: September 3rd 2020 by Scribner

|

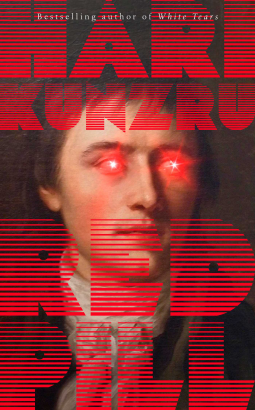

| The painting of Kleist (by Anton Graff) on which the novel's psychedelic cover is based |

This Is a very interesting novel. After reading this nove, I am excited to visit the most haunted places in Berlin. A must-read novel for the ones who loves fiction.

ReplyDelete